Education centre

Investing to secure a healthy financial future can be a daunting challenge – the old adage that the value of investments can move down as well as up remains as true now as it ever did.

What investing means

Investing is when you put your money to work to help you meet your long-term financial needs. When you invest, you take more risk with your money than you do with a high street savings account, but for that risk you hope to have a greater chance of a higher long-term return.

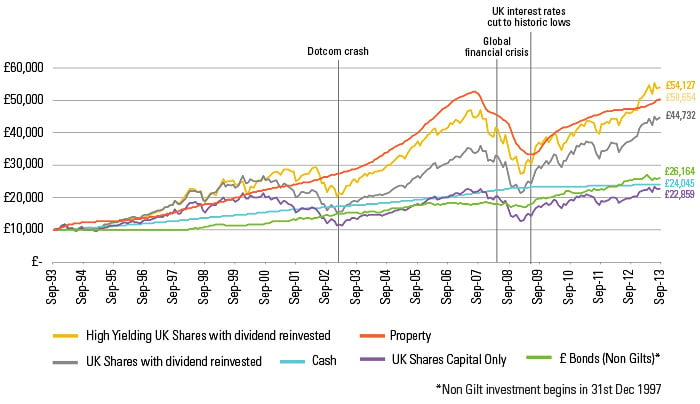

The value of £10,000 invested over the last 20 years.

There are many different types of investments and each has its pros and cons, but while investing can potentially help you grow your money, it can also result in you losing some or all of it. The chart shows the returns an investor could expect to receive having invested £10,000 over the last 20 years in various different investment types.

Source: Thomson Datastream and Threadneedle as at 30.09.2013. Cash represented by Three Month LIBOR rate. UK shares represented by FTSE All Share Index, capital return only. UK shares with dividend income reinvested represented by FTSE All Share Index, with dividends reinvested. High yielding UK shares with dividend income reinvested represented by FTSE 350 Higher Yield Index, with dividends reinvested. £ Bond (Non Gilts) represented by IBOXX £ Non Gilts All Maturities. Property is represented by Investment Property Databank (IPD). For illustration purposes only.

The returns from each type of investment go through peaks and troughs over the years. The chart illustrates that choosing the right asset class, depending on your investment goals and timeframes is critical. The chart uses market indices so does not necessarily reflect what an investor would have received by investing in a collective fund. The figures represent the actual returns from each index and do not include any charges, fees or taxation levies, that an investor would expect to incur. It is not possible to invest directly in these indices. There are different risk factors involved when investing in equities compared with cash deposits and investors are reminded that the value of investments and any income from them can go down as well as up. Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

Should you invest?

Before you invest you need to ask yourself whether it’s the right time. Generally, people are in a better position to invest if they have paid off debt, have adequate pension provisions, and have already accumulated enough cash in savings to cover any short-term expenses or financial goals, such as car repairs, holidays, home maintenance etc.

If you have all that covered, you are likely to be in a better position to invest for the longer term and assess your attitude to risk. In order to get a better return, an investor must take on more risk, which usually means investing in something riskier than a bank or building society savings account. Taking greater risk with your savings can potentially help you to grow your money faster over the long term, but there is a danger you could lose some or all of your cash.

To help reduce the risk, a sensible investor usually constructs a diversified portfolio that is spread among a number of different types of investment (also known as asset classes). Asset allocation – the practice of dividing your investment portfolio among different assets such as cash, equities, bonds, property and commodities – is the key to aiming to smooth your overall returns. The theory is that you reduce your overall risk of losing money because each asset class has a different correlation to the others; for example when shares rise, people may find bonds less attractive so the prices may often fall. At a time when the stock market begins to fall, investors may seek to invest their money in ‘real’ assets such as gold or property. By diversifying a portfolio investors will seek not to second guess these fast moving markets where one asset outperforms another and then falls back, but by smoothing overall returns with a portfolio containing a mixture of these assets.

To truly diversify investors should look to diversify within each asset class they own too. Looking at shares alone, for example, investors could spread their investments between large and small companies, between UK and overseas companies, and across sectors that are likely to perform differently at different times such as the retail sector versus pharmaceuticals.

Understanding your own attitude to risk will help you pick investments that deliver the return you expect. Think about your investment objectives and timeframe – the more time you have, the more risk you may be able to take. Consider your risk appetite: higher returns often mean higher volatility and higher risk, but if you can’t stomach losing money then you shouldn’t look to take on too much risk.

Types of investment

Investors can choose to invest in anything from savings accounts and property, to the stock market and fine wine. Only by learning about each can you make an informed decision as to which asset you feel most comfortable investing in.

Definition

Cash is the stuff that sits in your back pocket or your purse and can be deposited in current accounts and savings accounts. Sophisticated fund managers can also keep investors’ money in cash. They might hold a tiny part of an investment fund in cash to keep it safer than other assets, or they might run a fund that only invests in cash deposits.

Main characteristics

Cash is a safer asset than, say, shares or bonds, so the returns are typically smaller. In theory a bank could fail, but the Financial Services Compensation Scheme (FSCS) guarantees £85,000 per person on deposits, per authorised bank or building society.

Risks

The main risk with cash is that the returns are usually far lower than with other assets, making it more likely to be eroded by inflation. Think of a basket of goods worth £100 today. If inflation was 2% consistently, in 40 years time you would need approximately £220 to buy the same basket of goods. If you are investing for the long term and need to generate an inflation-busting return you need to find an account that beats inflation.

Definition

An equity, also known as a share, gives investors a stake in a company. If the company does well the value of the shares may rise and you may be able to sell them at a profit. However, they may also fall, making them a high-risk asset. Shareholders are also entitled to share in any profits made by a company, which are usually distributed in the form of a dividend payment.

Main characteristics

Equities can be bought and sold on stock exchanges around the world – in the UK alone there is a vast array of company shares to choose from. Investors can make a return when the price of a share goes up (though some sophisticated investors can actually bet on a share price falling) and also if the company distributes a share of its profits through income payments called ‘dividends’. Not all companies that make a profit pay dividends, however – they may choose, for example, to reinvest that profit in the business.

You can also buy equities listed on stock exchanges around the world, from the more developed markets of the US, Europe and Japan to high-risk developing markets such as Brazil, Russia, India and China.

Risks

A company’s share price can be affected by a huge number of factors, from the number of products a company sells to issues that affect whole national economies – making equities a risky investment. If the company doesn’t do well, you may not get any dividends and the value of the shares could fall or, in some cases, cease to have any value at all. If the company went bankrupt all shares are likely to be worthless. As there is a chance you might not get your money back, equities are considered higher-risk investments.

However, they also have the potential to make a generous return, making them a popular choice of asset for most investors looking to invest for the long term, whether directly or via a collective investment fund.

Definition

Bonds are loans to companies, local authorities or the government. So you lend your money to a company or government and you are paid interest in return. They usually pay a fixed rate of interest each year (known as the coupon) and aim to pay back the capital at the end of a stated period (known as the maturity date). This is why bonds are sometimes referred to as fixed interest.

Main characteristics

Corporate bonds are issued by companies such as Tesco and BT Group as a way of raising money to invest in their business. Government bonds are issued by a government – in the UK these are known as gilts. Once a bond has been issued, it can be traded on a stock exchange, where the price will rise or fall based on supply and demand; while it can also be influenced by the wider economy and investor predictions of how bank interest rates will change.

Risks

You will usually receive a smaller coupon from institutions that are more creditworthy and a larger coupon from those less creditworthy, reflecting the higher risk that they might not pay you back. The amount of interest a bond or gilt pays is fixed, which means that if interest rates fall they can become more attractive; though if interest rates rise they become less attractive, as investors may not be willing to accept the extra risk for less return compared to savings accounts if the coupon is not much higher.

Definition

Investors can invest in the buy-to-let market or commercial property – shops, offices and industrial warehouses, usually accessed via a collective fund of some type rather than directly. Investors benefit from rental income and the price of the property itself should it rise in value.

Main characteristics

Commercial property is very different from residential property (i.e., the house we buy, sell and live in) and does not always rise and fall in line with residential property market movements.

Risks

The value of the property itself could fall in value, while buildings might remain empty, meaning there will be no tenants to pay rent. Moreover, commercial property is not a ‘liquid’ investment, meaning it can be difficult to buy and sell property quickly and easily and valuations are based on opinions, not fact, as property is difficult to value accurately and costs a lot of money to buy and sell. But many investors like to include some property in their portfolio because it helps them to diversify: for example, investors might still receive rental income even if equity dividends fall and vice versa.

Definition

Commodities are raw materials for production: agricultural products such as wheat and cattle, energy products such as oil and gasoline, and metals such as gold, silver and aluminium. There are also “soft” commodities, or those that cannot be stored for long periods of time, which include sugar, cotton, cocoa and coffee.

Main characteristics

Whether it’s metals, energy or agricultural products, commodities are often traded on a ‘futures market’, where buyers purchase the obligation to receive a specific quantity of the commodity at a specific date and price. This helps protect commodity producers because it often takes a long time to produce, say, grain, and during that time prices could fluctuate dramatically.

Risks

Commodities are generally considered to be riskier than other assets and are highly volatile. They are very dependent on outside forces such as the wider economy, or political issues, such as oil in the Middle East. They are therefore only suitable for sophisticated investors.

Collective investments

Instead of buying assets – such as equities – directly, investors can pool their cash with others by investing in a collective investment, such as a fund. They invest across a wide range of companies, sectors, countries and, often, other funds.

Collective funds allow investors to diversify their assets at the same time as accessing the experience of a professional fund manager. Investors can invest lump sums of as little as £1,000 or set-up regular savings plans from as little as £50 a month. Please note that these sums vary between groups – always check before investing.

Collective funds are sometimes grouped into geographical areas such as the UK, Europe, the US or Far East, and are further categorised by their investment strategy such as Growth or Income . There are thousands of funds split into many different sectors. The most common type of collective investments are collective investment schemes such as unit trusts/open ended investment companies (OEICs) and investment companies.

A unit trust is an investment fund shared by lots of different investors. The fund is divided into segments called ‘units’, which investors buy to own a stake in the fund. The price of each unit is based on the value of the assets owned by the fund. Unit trusts are open-ended, meaning they get bigger as more people invest and smaller as investors withdraw their money. There are usually two different prices, making a unit trust a “dual priced fund”.

The two prices are:

- The ‘offer’ price – the price you pay to buy units, and;

- The ‘bid’ price – the price you get for selling units.

The difference between the buying and selling prices is the bid/offer spread, which broadly comprises the initial charge plus the difference between the buying and selling prices of the underlying investments plus any other costs involved in buying or selling the underlying investments.

This means that when investments are bought or sold as a result of other investors joining or leaving the fund your investment is sheltered from the costs of these transactions. The buying (offer) and selling (bid) prices of the fund are generally dependent on whether more people are buying units in the fund than selling, and vice versa.

Open-ended investment companies (OEICs) work in the same way as unit trusts but package their investments into shares – not units – and have a single price, so there is no bid/offer spread. Like a unit trust, an OEIC is open-ended so the size of the overall fund will get bigger or smaller as more or less people invest. Sometimes, a fund manager will charge investors in a single priced fund a “dilution levy” or “adjustment”. This is done to protect existing shareholders from the costs of buying or selling underlying investments, as a result of large investors joining or leaving the fund. A dilution adjustment affects everyone who deals on a particular day when there are large investors joining/leaving the fund, whereas a dilution levy only affects the individuals who trigger the price movement.

Offshore funds work in the same way as unit trusts or OEICs, but are domiciled in an offshore territory (such as the British Virgin Islands or the Cayman Islands) where the tax regime is often favourable to the investment manager or the investor. Income in the form of dividends, for example, can be subject to less tax than it would in a UK-domiciled fund. This tax-free income can be reinvested for even greater capital gains.

But while the tax advantages can lead to increased performance or a higher level of income, offshore funds are sometimes not subject to the same rigorous financial regulation as domestic funds, making them generally higher-risk – and not ideally-suited for beginner investors.

Investment trusts are similar to unit trusts and OEICs in that they invest in shares, bonds or property and provide the opportunity for investors to spread risk. However, when you invest in an investment trust you are buying shares in a company – not units in a fund. Investment trust shares are quoted on the stock market and are thus publicly traded in the same way as equities. You take a stake in an investment trust by buying its shares.

Investment trusts are ‘closed-ended’ funds because there are a set number of shares and this number does not change regardless of the number of investors.

Investment trusts are considered slightly higher risk than unit trusts and OEICs because they are allowed to borrow money to invest – this is called ‘gearing’. An investment trust that is geared is a higher-risk investment than one that is not geared because the manager has borrowed that extra cash with which to invest.

Investment trusts are considered slightly higher risk than unit trusts and OEICs because they are allowed to borrow money to invest – this is called ‘gearing’. An investment trust that is geared is a higher-risk investment than one that is not geared because the manager has borrowed that extra cash with which to invest.

But while gearing can make investment trusts higher-risk, a manager who is highly-geared is likely to have a strong conviction that what he is investing in is a good prospect – or he wouldn’t take on that additional risk.

The value of the assets held by an investment trust may be different from the actual share price, which means their shares can trade at a discount or a premium to the value of the underlying assets. This exaggerates the pattern of share price performance – both upwards and downwards when compared to returns from unit trusts and OEICs.

If you are unsure whether investing in an investment trust is right for you, speak to a financial adviser.

Asset allocation

You must make sure you review your portfolio regularly because the right asset allocation for your needs will change over the years as your investment goals change.

For example, when you are in your twenties and starting investing for retirement you might have a high proportion of your money in equities, as you have 30+ years to ride out the peaks and troughs of the stock market. When you are retired you will concentrate on generating income from your capital and trying not to let your capital deplete too fast, so you may move more of your portfolio into bonds.

It is up to you to make sure your investments are still meeting your objectives as you move through life. But just as your goals may change, so your investments will go through periods of under and over-performance. This means you should always keep on top of your investments to ensure they are performing adequately.

Multi-manager funds / multi-asset funds

As the name suggests, Multi-manager funds invest in a number of underlying funds, which in turn invest in a range of different companies across varying sectors, regions and asset types . A Multi-manager will research these funds and select a blend of what he believes are the best funds available into one single fund.

Multi-manager funds come in two types:

Funds of funds invest in existing unit trusts, OEICs or investment trusts run by other fund managers.

Manager of managers give a selection of external managers a chunk of money to manage.

There will be a pre-set framework for the fund, which dictates how much of the portfolio should be given over to equities, fixed interest and other asset classes. The fund manager then decides which firms and managers have the best skills to run each part of the portfolio and hands out mandates telling each manager how their particular part should be run.

There are also hybrid multi-manager funds that use a mixture of both strategies.

Multi-asset funds invest across the asset classes and are categorised according to the mix of assets the manager invests in (i .e . what percentage of equities, shares, bonds and property he holds).

Charges and costs

When you buy a collective investment, there is a range of fees applicable, depending on how you invest.

For beginner investors, the thought of investments falling in value can be far more worrying than it is for experienced investors – usually because beginners have not fully analysed their attitude to risk. Learning about financial products and understanding the risk and rewards on offer can help even the most inexperienced investor to make informed investment decisions.

Initial fees: A one-off fee charged at the time you buy the fund. These have in the past been as high as 5.5% of the sum invested. A portion of this fee was typically used to pay financial adviser commission. However, advisers can no longer accept commission in this way due to legislation called the Retail Distribution Review (RDR). For this reason and also increased competition from discount brokers and fund supermarkets/platforms, initial charges have largely disappeared.

Ongoing charges figure (OCF): The OCF is an industry wide standard calculation that illustrates most fees and charges borne by a fund. This figure is used by investors as it offers a single snapshot of how much you are paying for a fund and makes it easy to see the impact of charges on returns.

The OCF is based on the last year’s expenses and may vary from year to year. It includes charges such as the fund’s annual management charge, registration fee, custody fees and distribution cost but excludes the costs of buying or selling assets for the fund (unless these assets are shares of another fund).

Annual management charge (AMC): This annual fee covers the cost of fund management. The AMC tends to be around 1% – 1 .5%. Actively managed funds tend to have higher annual management fees, while tracker (passive) funds tend to have lower charges.

Performance fees: Some actively managed funds may levy a performance fee, though this is a small and decreasing number of funds.

Investors should note that these charges can vary considerably.

How to invest

There are a few different ways in which investors can buy funds: direct from the fund manager, via a fund platform, or via a financial adviser.

A fund manager will usually levy an initial charge so it makes sense to use an adviser, a broker or a fund platform which allows you to compare and purchase different investments online.

An independent financial adviser will help you choose what to invest in, and will discuss your financial goals, your attitude to risk and advise you of the most appropriate investment for your circumstances.

If you have decided what to invest in yourself and do not need advice, you can use a broker (who does not give advice – also known as an execution-only broker or a discount broker), through which you can invest in funds, investment trusts, Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) and other assets.

You may also like

Types of investment

We offer a broad range of actively managed investment strategies and solutions covering global, regional and domestic markets and asset classes.

Our funds

Columbia Threadneedle Investments has a comprehensive range of investment funds catering for a broad range of objectives.

About us

Columbia Threadneedle Investments is a leading global asset management group that provides a broad range of actively managed investment strategies and solutions for individual, institutional and corporate clients around the world.